| Welcome

To Our "Selected Works of Kurt Saxon & Other Fine Folk" Section |

This

is why I fear an EMP attack against the United States.

Read and heed!

![]()

E-Bombs

Part 1

of 4

In

the blink of an eye, electromagnetic bombs could throw civilization back 200

years. And terrorists can build them for $400.

BY

JIM WILSON

Lead illustration by Edwin Herder

The

next Pearl Harbor

will not announce itself with a searing flash of nuclear light or with the

plaintive wails of those dying of Ebola or its genetically engineered twin. You

will hear a sharp crack in the distance. By the time you mistakenly identify

this sound as an innocent clap of thunder, the civilized world will have become

unhinged. Fluorescent lights and television sets will glow eerily bright,

despite being turned off. The aroma of ozone mixed with smoldering plastic will

seep from outlet covers as electric wires arc and telephone lines melt. Your

Palm Pilot and MP3 player will feel warm to the touch, their batteries

overloaded. Your computer, and every bit of data on it, will be toast. And then

you will notice that the world sounds different too. The background music of

civilization, the whirl of internal-combustion engines, will have stopped. Save

a few diesels, engines will never start again. You, however, will remain

unharmed, as you find yourself thrust backward 200 years, to a time when

electricity meant a lightning bolt fracturing the night sky. This is not a

hypothetical, son-of-Y2K scenario. It is a realistic assessment of the damage

the Pentagon believes could be inflicted by a new generation of

weapons—E-bombs.

The

first major test of an American electromagnetic bomb is scheduled for next year.

Ultimately, the Army hopes to use E-bomb technology to explode artillery shells

in midflight. The Navy wants to use the E-bomb’s high-power microwave pulses

to neutralize antiship missiles. And, the Air Force plans to equip its bombers,

strike fighters, cruise missiles and unmanned aerial vehicles with E-bomb

capabilities. When fielded, these will be among the most technologically

sophisticated weapons the U.S. military establishment has ever built.

There

is, however, another part to the E-bomb story, one that military planners are

reluctant to discuss. While American versions of these weapons are based on

advanced technologies, terrorists could use a less expensive, low-tech approach

to create the same destructive power. “Any nation with even a 1940s technology

base could make them,” says Carlo Kopp, an Australian-based expert on

high-tech warfare. “The threat of E-bomb proliferation is very real.”

POPULAR MECHANICS estimates a basic weapon could be built for $400.

An

Old Idea Made New

The theory behind the E-bomb was proposed in 1925 by physicist Arthur H.

Compton—not to build weapons, but to study atoms. Compton demonstrated that

firing a stream of highly energetic photons into atoms that have a low atomic

number causes them to eject a stream of electrons. Physics students know this

phenomenon as the Compton Effect. It became a key tool in unlocking the secrets

of the atom.

Ironically,

this nuclear research led to an unexpected demonstration of the power of the

Compton Effect, and spawned a new type of weapon. In 1958, nuclear weapons

designers ignited hydrogen bombs high over the Pacific Ocean. The detonations

created bursts of gamma rays that, upon striking the oxygen and nitrogen in the

atmosphere, released a tsunami of electrons that spread for hundreds of miles.

Street lights were blown out in Hawaii and radio navigation was disrupted for 18

hours, as far away as Australia. The United States set out to learn how to

“harden” electronics against this electromagnetic pulse (EMP) and develop

EMP weapons.

America

has remained at the forefront of EMP weapons development. Although much of this

work is classified, it’s believed that current efforts are based on using

high-temperature superconductors to create intense magnetic fields. What worries

terrorism experts is an idea the United States studied but discarded—the Flux

Compression Generator (FCG).

A

Poor Man’s E-Bomb

An FCG is an astoundingly simple weapon. It consists of an explosives-packed

tube placed inside a slightly larger copper coil, as shown below. The instant

before the chemical explosive is detonated, the coil is energized by a bank of

capacitors, creating a magnetic field. The explosive charge detonates from the

rear forward. As the tube flares outward it touches the edge of the coil,

thereby creating a moving short circuit. “The propagating short has the effect

of compressing the magnetic field while reducing the inductance of the stator

[coil],” says Kopp. “The result is that FCGs will produce a ramping current

pulse, which breaks before the final disintegration of the device. Published

results suggest ramp times of tens of hundreds of microseconds and peak currents

of tens of millions of amps.” The pulse that emerges makes a lightning bolt

seem like a flashbulb by comparison.

An

Air Force spokesman, who describes this effect as similar to a lightning strike,

points out that electronics systems can be protected by placing them in metal

enclosures called Faraday Cages that divert any impinging electromagnetic energy

directly to the ground. Foreign military analysts say this reassuring

explanation is incomplete.

The

India Connection

The Indian military has studied FCG devices in detail because it fears that

Pakistan, with which it has ongoing conflicts, might use E-bombs against the

city of Bangalore, a sort of Indian Silicon Valley. An Indian Institute for

Defense Studies and Analysis study of E-bombs points to two problems that have

been largely overlooked by the West. The first is that very-high-frequency

pulses, in the microwave range, can worm their way around vents in Faraday

Cages. The second concern is known as the “late-time EMP effect,” and may be

the most worrisome aspect of FCG devices. It occurs in the 15 minutes after

detonation. During this period, the EMP that surged through electrical systems

creates localized magnetic fields. When these magnetic fields collapse, they

cause electric surges to travel through the power and telecommunication

infrastructure. This string-of-firecrackers effect means that terrorists would

not have to drop their homemade E-bombs directly on the targets they wish to

destroy. Heavily guarded sites, such as telephone switching centers and

electronic funds-transfer exchanges, could be attacked through their electric

and telecommunication connections.

Knock out electric power, computers and telecommunication and you’ve destroyed the foundation of modern society. In the age of Third World-sponsored terrorism, the E-bomb is the great equalizer.

In the 1980s, the Air Force tested E-bombs that used cruise-missile delivery systems. PHOTO BY AVIATION WEEK & AEROSPACE TECHNOLOGY

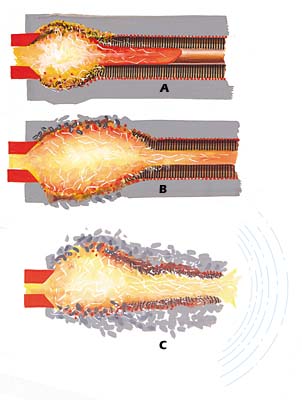

To ignite an E-bomb, a starter current energizes the stator coil, creating a magnetic field. The explosion (A) expands the tube, short-circuiting the coil and compressing the magnetic field forward (B). The pulse is emitted (C) at high frequencies that defeat protective devices like Faraday Cages.

ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN BATCHELOR

![]()

ELECTROMAGNETIC

BOMB

A

WEAPON OF ELECTRONIC MASS DESTRUCTION

WRITTEN

BY CARLO KOPP, DEFENSE ANALYST, MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA

High

Power Electromagnetic Pulse generation techniques and High Power Microwave

technology have matured to the point where practical E-bombs (Electromagnetic

bombs) are becoming technically feasible, with new applications in both

Strategic and Tactical Information Warfare. The development of conventional

E-bomb devices allows their use in non-nuclear confrontations. This paper

discusses aspects of the technology base, weapon delivery techniques and

proposes a doctrinal foundation for the use of such devices in warhead and bomb

applications.

Introduction

The

prosecution of a successful Information Warfare (IW) campaign against an

industrialised or post industrial opponent will require a suitable set of tools.

As demonstrated in the Desert Storm air campaign, air power has proven to be a

most effective means of inhibiting the functions of an opponent’s vital

information processing infrastructure. This is because air power allows

concurrent or parallel engagement of a large number of targets over

geographically significant areas.

While

Desert Storm demonstrated that the application of air power was the most

practical means of crushing an opponent’s information processing and

transmission nodes, the need to physically destroy these with guided munitions

absorbed a substantial proportion of available air assets in the early phase of

the air campaign. Indeed, the aircraft capable of delivering laser guided bombs

were largely occupied with this very target set during the first nights of the

air battle.

The

efficient execution of an IW campaign against a modern industrial or

post-industrial opponent will require the use of specialised tools designed to

destroy information systems. Electromagnetic bombs built for this purpose can

provide, where delivered by suitable means, a very effective tool for this

purpose.

The

EMP Effect

The

ElectroMagnetic Pulse (EMP) effect was first observed during the early testing

of high altitude airburst nuclear weapons. The effect is characterised by the

production of a very short (hundreds of nanoseconds) but intense electromagnetic

pulse, which propagates away from its source with ever diminishing intensity,

governed by the theory of electromagnetism. The ElectroMagnetic Pulse is in

effect an electromagnetic shock wave.

This

pulse of energy produces a powerful electromagnetic field, particularly within

the vicinity of the weapon burst. The field can be sufficiently strong to

produce short lived transient voltages of thousands of Volts (i.e. kiloVolts) on

exposed electrical conductors, such as wires, or conductive tracks on printed

circuit boards, where exposed.

It

is this aspect of the EMP effect which is of military significance, as it can

result in irreversible damage to a wide range of electrical and electronic

equipment, particularly computers and radio or radar receivers. Subject to the

electromagnetic hardness of the electronics, a measure of the equipment’s

resilience to this effect, and the intensity of the field produced by the

weapon, the equipment can be irreversibly damaged or in effect electrically

destroyed. The damage inflicted is not unlike that experienced through exposure

to close proximity lightning strikes, and may require complete replacement of

the equipment, or at least substantial portions thereof.

Commercial

computer equipment is particularly vulnerable to EMP effects, as it is largely

built up of high density Metal Oxide Semiconductor (MOS) devices, which are very

sensitive to exposure to high voltage transients. What is significant about MOS

devices is that very little energy is required to permanently wound or destroy

them, any voltage in typically in excess of tens of Volts can produce an effect

termed gate breakdown which effectively destroys the device. Even if the pulse

is not powerful enough to produce thermal damage, the power supply in the

equipment will readily supply enough energy to complete the destructive process.

Wounded devices may still function, but their reliability will be seriously

impaired. Shielding electronics by equipment chassis provides only limited

protection, as any cables running in and out of the equipment will behave very

much like antennae, in effect guiding the high voltage transients into the

equipment.

Computers

used in data processing systems, communications systems, displays, industrial

control applications, including road and rail signalling, and those embedded in

military equipment, such as signal processors, electronic flight controls and

digital engine control systems, are all potentially vulnerable to the EMP

effect.

Other

electronic devices and electrical equipment may also be destroyed by the EMP

effect. Telecommunications equipment can be highly vulnerable, due to the

presence of lengthy copper cables between devices. Receivers of all varieties

are particularly sensitive to EMP, as the highly sensitive miniature high

frequency transistors and diodes in such equipment are easily destroyed by

exposure to high voltage electrical transients. Therefore radar and electronic

warfare equipment, satellite, microwave, UHF, VHF, HF and low band

communications equipment and television equipment are all potentially vulnerable

to the EMP effect.

It

is significant that modern military platforms are densely packed with electronic

equipment, and unless these platforms are well hardened, an EMP device can

substantially reduce their function or render them unusable.

The

Technology Base for Conventional Electromagnetic Bombs

The

technology base which may be applied to the design of electromagnetic bombs is

both diverse, and in many areas quite mature. Key technologies which are extant

in the area are explosively pumped Flux Compression Generators (FCG), explosive

or propellant driven Magneto-Hydrodynamic (MHD) generators and a range of HPM

devices, the foremost of which is the Virtual Cathode Oscillator or Vircator. A

wide range of experimental designs have been tested in these technology areas,

and a considerable volume of work has been published in unclassified literature.

This paper will review the basic principles and attributes of these technologies, in relation to bomb and warhead applications. It is stressed that this treatment is not exhaustive, and is only intended to illustrate how the technology base can be adapted to an operationally deployable capability.

Explosively

Pumped Flux Compression Generators

The

explosively pumped FCG is the most mature technology applicable to bomb designs.

The FCG was first demonstrated by Clarence Fowler at Los Alamos National

Laboratories (LANL) in the late fifties. Since that time a wide range of FCG

configurations has been built and tested, both in the US and the USSR, and more

recently CIS.

The

FCG is a device capable of producing electrical energies of tens of MegaJoules

in tens to hundreds of microseconds of time, in a relatively compact package.

With peak power levels of the order of TeraWatts to tens of TeraWatts, FCGs may

be used directly, or as one shot pulse power supplies for microwave tubes. To

place this in perspective, the current produced by a large FCG is between ten to

a thousand times greater than that produced by a typical lightning stroke.

The

central idea behind the construction of FCGs is that of using a fast explosive

to rapidly compress a magnetic field, transferring much energy from the

explosive into the magnetic field.

The

initial magnetic field in the FCG prior to explosive initiation is produced by a

start current. The start current is supplied by an external source, such a high

voltage capacitor bank (Marx bank), a smaller FCG or an MHD device. In

principle, any device capable of producing a pulse of electrical current of the

order of tens of kiloAmperes to MegaAmperes will be suitable.

A number of geometrical configurations for FCGs have been published. The most commonly used arrangement is that of the coaxial FCG. The coaxial arrangement is of particular interest in this context, as its essentially cylindrical form factor lends itself to packaging into munitions.

n

a typical coaxial FCG , a cylindrical copper tube forms the armature. This tube

is filled with a fast high energy explosive. A number of explosive types have

been used, ranging from B and C-type compositions to machined blocks of

PBX-9501. The armature is surrounded by a helical coil of heavy wire, typically

copper, which forms the FCG stator. The stator winding is in some designs split

into segments, with wires bifurcating at the boundaries of the segments, to

optimise the electromagnetic inductance of the armature coil.

The

intense magnetic forces produced during the operation of the FCG could

potentially cause the device to disintegrate prematurely if not dealt with. This

is typically accomplished by the addition of a structural jacket of a

non-magnetic material. Materials such as concrete or Fibreglass in an Epoxy

matrix have been used. In principle, any material with suitable electrical and

mechanical properties could be used. In applications where weight is an issue,

such as air delivered bombs or missile warheads, a glass or Kevlar Epoxy

composite would be a viable candidate.

It

is typical that the explosive is initiated when the start current peaks. This is

usually accomplished with a explosive lense plane wave generator which produces

a uniform plane wave burn (or detonation) front in the explosive. Once

initiated, the front propagates through the explosive in the armature,

distorting it into a conical shape (typically 12 to 14 degrees of arc). Where

the armature has expanded to the full diameter of the stator, it forms a short

circuit between the ends of the stator coil, shorting and thus isolating the

start current source and trapping the current within the device. The propagating

short has the effect of compressing the magnetic field, whilst reducing the

inductance of the stator winding. The result is that such generators will

producing a ramping current pulse, which peaks before the final disintegration

of the device. Published results suggest ramp times of tens to hundreds of

microseconds, specific to the characteristics of the device, for peak currents

of tens of MegaAmperes and peak energies of tens of MegaJoules.

The

current multiplication (i.e.. ratio of output current to start current) achieved

varies with designs, but numbers as high as 60 have been demonstrated. In a

munition application, where space and weight are at a premium, the smallest

possible start current source is desirable. These applications can exploit

cascading of FCGs, where a small FCG is used to prime a larger FCG with a start

current. Experiments conducted by LANL and AFWL have demonstrated the viability

of this technique.

The

principal technical issues in adapting the FCG to weapons applications lie in

packaging, the supply of start current, and matching the device to the intended

load. Interfacing to a load is simplified by the coaxial geometry of coaxial and

conical FCG designs. Significantly, this geometry is convenient for weapons

applications, where FCGs may be stacked axially with devices such a microwave

Vircators. The demands of a load such as a Vircator, in terms of waveform shape

and timing, can be satisfied by inserting pulse shaping networks, transformers

and explosive high current switches.

Explosive

and Propellant Driven MHD Generators

The

design of explosive and propellant driven Magneto-Hydrodynamic generators is a

much less mature art that that of FCG design. Technical issues such as the size

and weight of magnetic field generating devices required for the operation of

MHD generators suggest that MHD devices will play a minor role in the near term.

In the context of this paper, their potential lies in areas such as start

current generation for FCG devices.

The

fundamental principle behind the design of MHD devices is that a conductor

moving through a magnetic field will produce an electrical current transverse to

the direction of the field and the conductor motion. In an explosive or

propellant driven MHD device, the conductor is a plasma of ionised explosive or

propellant gas, which travels through the magnetic field. Current is collected

by electrodes which are in contact with the plasma jet.

The

electrical properties of the plasma are optimized by seeding the explosive or

propellant with suitable additives, which ionizes during the burn. Published

experiments suggest that a typical arrangement uses a solid propellant gas

generator, often using conventional ammunition propellant as a base. Cartridges

of such propellant can be loaded much like artillery rounds, for multiple shot

operation.

![]()