| How

To Grow Vegetables And Fruits By The Organic Method |

FOREWORD: Part Two

Attaining Gardening Success

Live out west? Have you given up gardening because you found it: (1) takes too much fertilizer and (2) takes too much water? Well, you can start in again. Experience has shown that in many western areas—especially in the southern sectors of California, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico—an abundance of vegetables for the householder's own use can be grown on an ordinary city lot, and on nearly a year-around basis.

How can this be done, economically? Simply by putting back into the ground organic materials which come from your own yard or home.

For example, there is the garden plot at the home of Mr. Tony Fido, in Burbank, California. This garden plot is about 25 feet long and from 10 to 15 feet wide. But from this small space Mr. Fido gets just about all of the vegetables that he and his wife can use. Indeed, he does better than that, because he told me, "We have so much that I put some into our freezer and give some to our children for their families!"

A large part of the soil in the nation's western or southwestern area is either sandy or a hard-packed, rocky, clay soil. Both types require considerable humus added to them. Besides its other important roles, this humus acts something like a sponge in absorbing water quickly and then retaining it so that the moisture oozes out slowly for plant roots to use.

What supplies this humus? Natural organic material that is found in any yard. When the Fidos moved into their home the back yard was nothing but fine, barren sand. Now it is a rich, dark loam. In his own case he made a start by digging in some rabbit manure. However, for many years he has put in nothing but compost. Compost piles are the answer for every backyard gardener in the western area. Since material for compost piles is available most of the year—or even all of the year—to western gardeners, that does make them lucky!

Tony Fido likes to put his organic materials in compost holes right along the edge of his garden, where it is handy. He covers the material with a layer of dirt and keeps it well watered to hasten the rotting process. Rotting or decomposing is necessary, of course, in order to break down the leaves or grass or whatever the material is to where it can be used again by living plants.

If you want to do even better with your compost piles, simply dig a hole about 2 or 3 feet wide by 4 or 5 feet long and 2 feet deep. Put in a layer of leaves, grass clippings, garbage, chopped up weeds, waste leaves or peelings from vegetables, or whatever organic material might be at hand. Over this layer of perhaps 3 inches in depth sprinkle some fish fertilizer. Cover this with an inch or so of dirt, then put in another layer of organic materials, sprinkle that with fish fertilizer and so on. Be sure to keep the pile well watered. The fish fertilizer also helps to break down the organic materials by encouraging bacterial action.

The point that Tony Fido likes to make is obvious and yet seemingly not understood too well by many would-be back-yard gardeners—that crops take natural elements out of the soil and so those natural elements must be returned to the soil. "I get sort of mad when I see neighbors put out leaves or grass to be hauled away," he said, "and then hear them complain because they can't grow much in their gardens!" Then he grinned and continued, "That's why we don't have a garbage disposal unit. For garbage is organic material, too, you know, and I put it back into my ground.'"

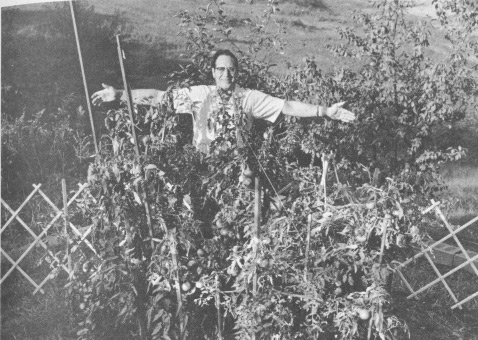

His garden is evidence of how well his fertilizing methods work. His vegetable crops are a healthy, dark green and so luxuriant that they are almost jungle-like in thickness. Before he plants each crop he spades some of his composted matter into the ground of his garden plot. "I spade the ground from 8 to 10 inches deep and I space the rows about that same distance apart," he said. "I can put the rows close together because there is plenty of plant food in the ground."

He grows an amazing variety of crops, many of them at the same time. In one year he will have carrots, celery, Italian leaf lettuce, turnips, spinach, onions, radishes, peas, beets, chard, cabbage, and other vegetables.

Early tomato plants are grown by Tony in a different way. He sets the plants out in very early spring, in holes that are from 6 to 8 inches deep, so that the sides of the holes retain moisture and also protect the tender plants against the chilly weather that sometimes hits even in this generally mild climate. He puts a shovelful of well-rotted compost under each plant, with a layer of dirt between the compost and the roots. As the plant grows, he puts more dirt into the holes to provide deeper rooting and greater strength. The plants are trained on wooden supports which give better growth and allow him to grow more of them in a smaller space.

Oh, yes—when the tomato crop has been picked, the vines are chopped up and put into the compost piles! This compost process comes as near to perpetual motion as it is possible to get. The things that grow are put back into the ground to help grow still more things.

Thus, you can see that there is no reason to complain about gardening in the west costing too much for fertilizer and water. You grow your own fertilizer and the use of this compost material cuts down on the amount of water you need. Now watch those gardens grow! —Ivan F. Hall

Giant Crops from a Midget Homestead

"The bulldozer stole 10 feet of our soil, but we built new soil—better than before."

So says Frank Fiederlein, organic gardener of New Britain, Conn, who has what is virtually a miniature homestead—on a lot 50 by 140!

"People just don't dream of the vast variety of vegetables and fruit they can grow organically on a small plot," says Frank. "They think they need loads of topsoil, bags of chemical fertilizers and all kinds of deadly sprays to grow anything at all.

"But we didn't need any of these things. In fact, we did not even have any topsoil to speak of on the part of our land that now raises our vegetables. But today we have a constant supply of fresh vegetables all through the growing season—plus all the fruit we can eat, a really lush lawn and a huge variety of flowers. And we never spent a cent on chemicals."

When Frank and Cecile Fiederlein moved into their new Cape Cod home 4 years ago, the grounds presented a real problem. The group of houses of which theirs is one is situated on a street cut along the side of a hill. In order to make the street and the rows of homes on each side of it level, the builders bulldozed a cut across the hillside.

This meant that a huge amount of soil was removed from the Fiederlein's place—to a depth of 10 feet in the rear.

|

|

Frank Fiederlein of New Britain, Connecticut points out the excellent quality of his soil which had once been only a poor mixture of sand and gravel. After several years of organic gardening, he now grows more produce than his family can eat. |

And what was left? "The worst collection of stones, sand and gravel you ever saw," says Frank.

But he had the answer.

"First we took out all the rocks, I used them to make a retaining wall on the bank at the back of our property. Stones and pebbles we removed to a low spot in a nearby woods, or saved for rock mulching.

"Then that autumn we started to build soil, using the trench method. We dug two-feet-wide trenches, about 12 to 14 inches deep. Having no manure, we mixed in half-decayed leaves and pine needles, with a little agricultural lime and cottonseed meal added."

The following spring, Frank planted some tomato plants (mulched with leaves and pine needles), string beans, cucumbers and carrots. The results were surprisingly good. "The tomatoes were the envy of the neighborhood.

Besides having enough for our family and friends, my wife put up 55 quarts for the winter."

In the fall of that year (1955), Frank again dug in semi-decayed oak, elm and maple leaves from the woods. He also occasionally buried small amounts of clean garbage—potato and carrot peels, lettuce and cabbage leaves and the like. Then during the winter he was able to get some fairly well-rotted turkey manure, which he spread after sieving. In the spring, small quantities of lime and potash and phosphate rock powders were incorporated into the soil.

"Without realizing it, I had prepared a welcome home for untold numbers of earthworms. Today I can't turn a spadeful of soil without finding as many as two dozen worms in it.

"And the crops—well, I was amazed. I had 20 tomato plants, grown from small packets of seed, that produced tremendous crops. Cecile put up 75 quarts from that 1956 garden. The peas were plentiful, my lettuce, radishes and spinach came in strong. Our supply of Tendergreen beans was constant. My Detroit Dark Red beets grew rapidly and were delicious. I had some wonderfully tasty long slim carrots, grown from seed requested from the Massachusetts Experiment Station. And the harvest of cucumbers from 4 hybrid vines was too much for the family.

"I knew my soil was really coming alive. It was starting to show a wonderful texture, open, well aerated and able to hold plenty of moisture. I could see it was becoming vital and healthy, not like the sad-looking dead stuff you so often see in gardens where chemicals are used."

That fall he put turkey manure on the vegetable plot, digging it in last spring. He also buries the turkey feathers—"they decay very quickly." Mulching materials are constantly applied throughout the growing season. Frank uses grass clippings, garden refuse, leaves and pine needles. A little lime is sprinkled on the pine needles to counteract their acidity. Virtually no weeding has to be done. The mulch is dug in in the fall.

He says there is still some slight unevenness in the texture of his soil, but this is gradually disappearing as more organic materials are incorporated. It is fast becoming a rich, dark loam, far from the dusty, light-colored sand it was originally. Soil tests this spring showed an abundance of nutrients.

The peas produced a bumper crop last year. Four kinds of lettuce, plus radishes, chives and beet greens filled out the vegetable supply through June.

The wax beans also came in in June, followed by green beans and then pole beans.

Between the tomato plants he grows red and white cabbage for coleslaw to replace the lettuce, which he will have again in the fall. This year the Fieder-leins have three varieties of tomatoes: Peron, a large beefsteak from Argentina;

San Marzano, a paste tomato; and Golden Sphere, a large yellow. The first two they combine for tomato sauce.

Frank's real pride and joy is his miniature orchard. In front of the house, as an integral part of the foundation planting, are growing two Hansen bush cherries and two bush plums. Spotted around the rear are 4 dwarf apples— Mclntosh, Cortland, Delcon and Red Delicious; two dwarf pears—Bartlett and Clapp's Favorite; two Montmorency cherries; two Korean cherries; two Oka cherries (a cherry-plum hybrid); 3 red currants—two Red Lake and one Wilder; 4 dwarf plums—Abundance, Burbank, Stanley and a Japanese-American hybrid. The last-named plum is growing, along with an Elberta peach, on the bank behind the retaining wall (Frank has also extended the size of his vegetable garden by planting his peas and cucumbers on the bank.)

All of these are doing very well. "The currants bore well last year, and now the dwarf apples and pears and the cherries are starting to come in. Very soon now we will have a plentiful supply of tasty, all-organic fruit in enormous variety.

"Here's a funny thing: the nurseryman told me my Korean cherries would not grow more than 5 to 6 feet high. Already they're over 9 feet tall!"

Another heavy producer is his blueberry bed. A little over 50 feet long, it contains 13 plants of 6 different varieties (to insure a long harvest).

"To make the blueberry bed, I dug out a trench 4 feet wide and about 18 inches deep. I filled it with the top 2 or 3 inches of soil from under some pine trees, plus pine needles, sawdust, semi-decayed leaves and sand. Around the roots I used a mixture of sand, loam and peat moss. Each year I add a two-inch layer of pine needles. The yields are getting better all the time."

The rich lushness of his lawn, despite drought and a municipal ban on watering, is another accomplishment of which Frank is justly proud. He ! spreads compost on it in early fall, then lightly applies sieved turkey manure on top of the snow or just before a spring rain. The excess is later gathered. By mid-April he had cut the velvet carpet 4 times, which amazed his neighbors no end.

Frank and Cecile grow some 22 annuals in their flower beds, and have a bed of low-growing mums fronting their property—a real car-stopper during blooming season. They are also starting perennials in a bed behind the retaining wall, and have interplanted tulips under the bush plums and cherries. Along the east wall of the house they have also planted 3 filbert nut trees.

Both their adopted daughters. Nancy and Laurie, have their own tiny gardens, and are learning to grow vegetables and flowers the organic way. Every facet of the garden seems to fascinate them—and there's no danger from poisonous chemicals anywhere on the place!

"Everything grows like magic with organics," Frank says. "Three years ago I bought some tiny cactus plants from the five-and-dime. Now one of them is over 4 feet tall."

He stopped to think a moment. "You know, there are untold numbers of homeowners who could and would put their back yards to good use hobby-wise and health-wise, if only they had the know-how. With natural methods, they would—as I did—find it easy to produce huge yields of a vast Variety of crops from a small space.

"I treat the soil with enlightened respect and take good care of its marvelous inhabitants. In return, my garden rewards me a hundredfold, not only in

produce, but also in satisfaction and untold delight." —Betty Sudek

We Retired "Down South" in Florida

Five years ago, we came down here to southwest Florida to live beyond the reach of snow, sleet, blizzards and big fuel bills. It is nice to be able to go fishing comfortably almost any day in the year, never to wear an overcoat, never put antifreeze in the radiator.

Best of all, it is nice to be able to bring in something from our organic garden and orchard for any meal in the year. We have ripe citrus fresh off the trees eight months a year, bananas and papayas a few steps from the kitchen ten months of the year, and vitamin-rich fresh vegetables, too. We raise our own beef, chickens and eggs.

We can go dig a peck of Allgold sweet potatoes any time we want them— they keep growing all year long down here—and as I sit here typing we have three more months of late oranges on the trees, two more months of grapefruit, more tomatoes than we can eat or give away, sweet corn, watermelons, turnip greens (the wife is an Alabama gal), lettuce, cucumbers, squash, figs, three kinds of bananas—two dessert kinds and the baking variety—papayas, Surinam cherries, Irish spuds, pole beans, chayotes, flavoring herbs, all of these things organically grown, of course.

Any time I feel like mowing off the tall, bushy asparagus tops and dressing the bed with some compost, I can trim a peck or so of nice, tender shoots before letting the tops grow out tall again. The bees make honey nearly all year long, too. The family is healthy, full of pep, and able to enjoy life outdoors tour times as much as folks who live 'way up near the North Pole in such places as Michigan or northern California.

I am a Lieutenant Colonel on the Retired List of the Regular Air Force, having been retired for combat disability in 1947. During 20 years of active duty, I have traveled all over the world, always following my hobby of observing growing things and culture methods under various conditions of soil, climate, folklore, and the loss or maintenance of fertility.

Down here in Florida I have seen so many tragic results of basic ignorance of soil ecology and plant growth. For instance, here in Fort Myers the fine botanical garden planted on 14 acres of Thomas Edison's winter home loses many fine specimens each year because they try to grow everything from exotic tropicals to giant banyan trees with chemical fertilizers and have one employee whose duty is to clean up every leaf that falls, all shrubbery trimmings and grass cuttings, and either burn them or haul them away.

To a lesser extent, the same stupid formula is found in the famous Fairchild Gardens in South Miami; however, they do mulch a little, not for plant nutrition but as they explained, it keeps down the weeds! Up in the central and northern part of the state, older citrus groves are being bulldozed out and burned at taxpayer's expense due to heavy infestations of the nematode. This Pest is a logical result of heavy applications of corrosive fertilizers that have destroyed the soil's ecological balance and the earthworms so that there is nothing to hinder the spread of the nematodes.

Folks are moving down here by the thousands, but there is so much space left that there will be room for many more in the years to come. Unfortunately, there are sharp operators who take unkind advantage of the natural desire of older folks to retire to live inexpensively on modest incomes. These people advertise up north in newspapers, magazines, radio and TV, loudly promoting their "planned communities" and "subdivisions," many of which have only recently been bulldozed out of palmetto scrub wilderness 15 to 30 miles from town.

The wiser folks will take their time in coming here and looking around a good long while before buying a homesite. Organic gardeners want suitable soil for trees and gardens, not swampy lowland that will be under standing water many months during the late summer and fall rainy season. They will get acquainted with people who live here all year around, and stay away from the high-pressure promoters who want to sell them poor land and badly built houses for much more than they could ever be worth.

In my own case, I found that by looking around a few weeks before buying, I was able to get 23 acres of an old orange grove right on a big river, for no more than two acres would have cost me at promoter's prices. I am closer to town than several of these "planned communities," have richer soil than any of them, better drainage in wet weather, and no restrictions. In some highly advertised developments, most folks cannot afford the land area needed for a small family-size citrus grove and garden, and most of them will not allow compost piles, bee hives, chickens, milk cows or goats or much of anything any proper organic gardener wants for comfortable and healthful living.

Many older couples now come in a modest house trailer pulled by a pickup truck. They find a nice homesite, buy it, get electric service, have an artesian well driven, then start their retirement home with no hurry and nobody to disturb their careful and leisurely planning, tree planting, and building. Many of these fine folks build their own homes, working slowly as energy and finances permit, enjoying every minute of it, and saving nearly two-thirds of the cost of hiring the work done.

You may say at this point: "I never built anything; I wouldn't know how." Well, pardner, tnere are lots of folks here with less talent and strength than you, and they proudly live in some extra nice homes they built with their own hands. If you are smart enough to be an organic gardener, there is no limit to what else you can do.

One of my best friends up the river is a young fellow of 72 who has almost completed the nicest and most modern house in his neighborhood during the past year. I built my own home from footing to fireplace chimney top, including plumbing and electric wiring, cypress paneling, sliding doors, aluminum awning windows, concrete block walls, cedar framing and sheathing, sound-absorbing ceiling tile, big garage, two bathrooms plus asbestos shingle fireproof roof, built-in cabinets and ceiling fan. I laid every block and drove every nail and learned how to do the whole job while doing it. Of course you can do it, and save yourself several thousand dollars while having the time of your life.

Growing most anything down here in the subtropics is a little different from the way you did the job up north. It is warmer, more rain falls, vegetation grows faster, decays quicker, and there are more insects, soil fungi and nematodes. Simple organic methods work the same, however. Compost, mulch and earthworms solve any plant problem as long as drainage, shade and soil pH are under control. Heavy rainfall leaches out soluble plant foods from the soil; hot sunshine causes the nitrogen in organic matter to evaporate as ammonia unless protected by mulch.

All these lost plant foods may be recovered by adding floating water hyacinths or cattail grasses to the compost pile, and keeping the pile covered to prevent soaking away during the rainy season. Mulch your fruit trees with shavings, old boards, burlap, flat rocks or most anything else to prevent heavy grass and weed growth from robbing the surface roots. Lift up the mulch twice a year to add an inch or so of compost, and your neighbors will be amazed at the size and flavor of your fruit.

This treatment works equally well on bananas, papayas, or any of the dozens of tropical fruits from loquats to cherimoyas. Do these names sound strange to you? After a few months here they will be as familiar to you as apples and pears up north. You will get a real thrill out of showing your "Yankee" guests what you can grow with compost and earthworms: Watermelon vines that bear 8 or more fine melons each; tomato vines that cover the area of an army blanket and keep bearing grape-like bunches of sweet tomatoes for half a year; wild fruit in abundance such as guavas and wild grapes for excellent jams and jellies; or the tropical winged yam with tubers weighing 50 pounds or more. Flower lovers may have blossoms outdoors the year around, and foliage plants grow wonderfully out of doors in this climate.

Wild orchids bloom every summer hanging from oaks and hickory, and in the wet places wild iris in blue and yellow, compete with the soft lavender of floating water hyacinth blossom clusters. Out in the country where stupid spraying programs are avoided, swarms of hungry dragon flies sweep the mosquitoes from the air as fast as they hatch. In town and in the "planned communities" one must retreat behind screens each evening to avoid swarms of little and big mosquitoes since the spraying poisons both the dragon flies and mosquitoes hatching from the same water, and the mosquitoes simply hatch faster.

To sum it all up: You organic folks who want to retire in Florida, come down here and take your time looking around. Stay away from the "fast buck" promoters. Choose the kind of land, neighborhood and neighbors that add value to your choice of a homesite as the years go by. Bring along the old hammer, saw, level and pipe wrench, and build your own dream home, because you can do all or most of it with time and patience. As to growing anything down here, organic folks are the only ones who are completely successful year after year because they work with Mother Nature, not against her. —Oliver R. Franklin

"I Like to Work with Plain Dirt"

A white-haired little woman with a country girl's love of the good earth and the things it can yield is amazing her neighbors by harvesting a year's supply of vegetables from the dust of a city's streets.

She is Mrs. H. R. Leversee of Kalamazoo, Michigan, and for nearly 20 years she has turned a shovel, a wheelbarrow and the courage of her conviction into as beautiful and productive a back-yard garden as there is in the city.

|

|

|

(Above) Mrs. H. R. Leversee of Kalamazoo, Michigan dumps a wheelbarrow load of "dirt onto her back yard garden. (Below) Mrs. Leversee stands amid the multitude of vegetables and flowers which she grows in her garden with the help of that fertility-laden "din" which she collects daily from the neighborhood. |

Mrs. Leversee s source of dirt for her garden is unorthodox to say the least.

Every morning for the past 17 years, with the exception of the bitter cold days of winter, this amazing little woman has trundled her wheelbarrow into the streets of her neighborhood and shoveled up the dirt which always lines the gutters.

She fills up her wheelbarrow and rolls it back to her home where she spreads it over her back yard or lawn or wherever she needs it most. If it's a good day and she feels spry enough, she will make 2 or 3 trips up and down the streets in search of dirt. And sometimes she's even out in the evening.

She's never kept a record of her work, never thought it would interest anybody. But it's a safe bet that Mrs. Leversee, at an age when most women have slowed down to knitting a fast pair of mittens for a grandchild, has hauled at least 100 tons of dirt from gutter to garden in the last 17 years. It amuses her that anyone should care about her project.

"I know that a lot of my neighbors and others who see me out with my shovel and wheelbarrow think I'm crazy," she says with a smile.

"But I've reached the age where I don't care what others think. If I ever do have any doubts, all I have to do is look at my beautiful garden, my flowers, my cellar full of canned vegetables, and I know I'm right.

"You see, I was born in Arkansas. Down there everyone knows the value of earth. If you are lucky enough to own any, you guard it. My father never let a day pass that he didn't tell us that the earth took care of us and we had to take care of the earth.

"Up here it's different. Folks take their earth for granted. They buy expensive topsoil; it rains, the topsoil drains off into the gutters and they start over again buying more soil.

"If you just stop to think about it, any dirt in the city streets must be top dirt. It may look like dust and be full of grit and cinders, but it's rich and strong. It's a crime to let it flow into the sewers and be lost."

Mrs. Leversee, who attended college in Arkadelphia, Arkansas, and then taught school for years, came to Kalamazoo in 1926. In that time, using her unusual soil-salvaging system, she has raised the level of her lawn at least 6 inches above her neighbors' and turned her barren back yard into a living supermarket.

I've worn out three wheelbarrows in the process," says Mrs. Leversee, who has been a widow since 1947. "But look what I have.

I got over 23 dozen ears from 4 30 loot rows of corn this year," she states proudly. "I'll bet a lot of the people who stopped to buy a few ears from me are the same who let their own top dirt run off into the gutters."

The tireless little widow, who can't weigh much more than a bushel of Potatoes, cans a good share of her vegetables and then saves the balance of e gutter-born crop in a freezing unit which is as old as time. Each fall I dig a shallow hole in the garden. Then I put all extra vegetables in the hole in separate piles. The hole is lined with leaves and the vegetables are covered with leaves. Then I cover it all up with dirt.

"As the winter passes by I can go out to my natural 'deep freeze' and dig up fresh vegetables any time I want them."

This amazing little woman, a combination of pioneer, soil conservation expert, farmer and manual laborer, scoffs at the work involved in her dirt collecting and gardening.

"Working is like walking," she says. "If you enjoy it you never notice it.

I like to work with just plain dirt. I like to see things grow in it. Every shovelful I take from along the curbs will produce food some day. I'll never get tired of watching that happen." —Dan Ryan

Happiness in Gardening

When Paul Trucksis of Tipp City, Ohio, finally retired from his job at Deico Products Division of General Motors, he and his wife looked ahead for a worthwhile and health giving hobby. It was then that they became interested in gardening—organically.

In the past two years, he has proved with an abundance of flowers and vegetables that the organic method brings health, fun and profit. In fact, the family has so many flowers they're wondering where to put the next bed for transplanting.

He believes the following steps to be important to the organic gardener:

1. Have a "hidden" compost heap in the back yard where you make your humus. (Compost isn't enough—should be used with earthworms.)

2. Spade garden and cover with organic matter.

3. Plant seeds.

4. After plants have had a chance to grow a little, spread your own mulch around them. The earthworms work it into the soil.

"Once you provide the right soil for your plants (manure and organic matter homogenized by earthworms), you can just sit back and watch your garden grow," he says. "This organic type soil also resists weeds and it grows richer each year by nature's own work."

"I'm just a beginner," he smiles while leading the way through his gardens, "but I CAN tell you, that you, too, can have huge, tasty, Big Boy, acid-free tomatoes for EARLY market if you plant them organically." For vegetables, flowers or any planting, Trucksis mulches ground 4 to 6 inches all winter. Worms carry humus underneath, so no plowing is necessary. If soil is damp in spring there is no need to worry, things will grow.

He made over $100 ($374.20 2008 dollars) on 96 tomato plants on the early Dayton market when prices were best. Besides this, the family had plenty of the delicious, smooth fruit tor canning, preserving, for gilts to friends, and for table use. "It you're tomato-gardening tor profit, you want early market prices. Grow them organically and they'll be ready for early market."

"This is the happiest year of my life," Paul smiled as his wife, Mabel, nodded her approval. "If I can help others with my findings, I'm truly happy." And no one would guess this sincere organic gardener to be past retirement age for he appears 10 years younger. "We've never enjoyed life so much until we began gardening, truly organically," he says. —Clarissa Schweikert

A Help for Training Our Youth

The Grailville School, of Loveland, Ohio, believes that women have an essential role to play in the renewal of strength of modern society by contact with the earth. The purpose of this forward-looking institute for women is to give a vision of Christian womanhood and to apply this principle to modern young women in all spheres, of life.

Agriculture is included in the specialized apprenticeship offered to students —either short courses of a few weeks, or the more extensive, lasting a few years. From the training received here, the girls return to their former work or devote a part or all of their lives to the missionary fields for which they have been trained.

|

|

Lettuce and onions are shown being harvested in slope-planted fields by Grailville (Ohio} School students who not only learn to provide themselves with better food, but will also pass this knowledge along to people in other lands where they travel. |

Of special interest to gardeners is the training given the girls in agriculture. Here one can observe the wonderful results of putting into practice the teaching of organic gardening. An abundance of vegetables being harvested by the students leaves no doubt as to the superiority of their harvest and why they believe so profoundly in Nature's way of gardening to produce the best results.

Regardless of the course selected by the student, each one gets some practical training and understanding of gardening. In fact, each group has its own compost pile and sees to it that it is turned at the proper time.

The gardener pointed out one garden which was on a very slight slope.

Here the vegetables were planted on the contour. Even on so small a slope, she remarked of the absence of washing which she had observed with the conventional straight rows. Compost has been applied to all their gardens and mulching is practiced on most vegetables. The gardens are rotated each year and they supply most of the food for the 120 students enrolled during the year. One can well understand the reason for the 1,000 staked tomato plants, the many rows of beans, the abundance of herbs and the well-diversified gardens. Their mulched orchard provides much of their fruit. Any tree destroyed during the winter is replaced the following spring.

The 10 to 15 girls enrolled in agriculture usually attend for at least one year, so that they will have a practical understanding of gardening and the various phases of farming on the 380 acres of land. This group plants, tills and harvests the produce on the farm.

Watching these girls weeding the rows, picking the vegetables and fruits or turning the compost pile, one feels gratified to know that the principles of good gardening will be carried to near and far places; that with their missionary work in Christianity they will also be spreading the organic methods of good gardening and bringing back an awakening to the many peoples with whom they work that God's land cannot be neglected; that in the hearts and minds of the people must be a realization of the priceless heritage to build and maintain the fertility of our earth. —Marjean Headapohl

Pride in a Job Well Done

It was a very hot summer in McKeesport, Pennsylvania. Most plants were drying up and withering, and so Art Ryden kept an extra close watch on his Marglobe tomato seedling. And it turned out to be a truly fabulous one. Planted in the back yard compost pile, it grew 400 big, juicy tomatoes which totaled 100 pounds. The vine itself attained near record dimensions of 5 feet in height, 7 feet in length and 5 feet in width.

Pleasure in a Bountiful Garden

It may sound a little bizarre at first when you hear that Leroy T. Stratton encourages grass in his family garden. Or, looking at it another way—that he grows vegetables in his lawn.

Why should anyone alternate strips of lawn with strips of vegetables?

The most obvious reason, when you drop in on his place outside Rutland, Vermont, is the charming attractiveness of this setup. Here, the lawn doesn't end abruptly, but becomes lawn with neat beds of succulent edibles growing in it.

Yet Stratton is an intensely practical man (he used to be a banker) and he's not sacrificing food tor prettiness. Gardening the organic way, he wants the most food out of the least work. Besides quantity, there's quality—like6 his winning 6 out of 7 blue ribbons at a recent Rutland Fair.

So he's a master gardener, but a modern one. If he were back in the horse-team era, he'd need more elbow room for mowing machine and plow. But1 his power mower tor grass, and rotary tiller-type plow for vegetable beds make maneuvering easy—and his method adds up to less work instead of more. His third favorite "tool" is the compost pile.

|

|

Art Ryden of McKeesport, Pennsylvania proudly extends his arms to show the huge dimensions of a tomato plant which he started in a backyard compost pile. The vine grew 5 feet high and produced 400 tomatoes totaling more than 100 pounds. |

Since his climate is rugged and his soil wasn't much to begin with, here's a gardener well worth visiting for how-to tips.

Nine years ago, the site was just the corner of a rundown meadow near the house. Here, Stratton began with a few beds of vegetables. Stones were a problem, but he liked health-building exercise. Smaller ones were wheel-barrowed away. To handle a large boulder, he first built a brush fire on top of1 it, then dashed buckets of cold water upon the hot stone, thereby cracking it into pieces he could handle.

It was two-way traffic. Removing Stones, he brought back anything he could get in the way of fertile, humus-building material—grass, old hay, any manure that was available, plus enrichening compost. Result is the fine loam he has today, allowing close planting.

Meanwhile, when mowing lawn around the house, he kept on mowing-down those strips between vegetable beds. This kept down weeds, and as clippings decomposed, the grass grew greener. He found he was creating fine grassy walks.

This struck him as lots easier than cultivating between wide rows, or hand-pulling weeds between them. Mrs. Stratton was happy, too. Here was a garden that could be harvested without need to walk in soil that would track mud into the house—all the plots are easily reached from the grass carpet. Another advantage was space-saving. This part of the lawn was doing double duty.

Today, each grass strip is 40 inches wide, right size for cutting with one pass of the power mower's cutter blade. And there are 18 of the vegetable strips, each 54 inches wide. As a result, Stratton's gardening is divided into easy-to-handle bits.

Each of the 150-foot long strips holds, two, sometimes 3 rows of closely planted vegetables. This close planting compensates for space taken by the grass because Stratton can keep the soil highly fertile, using compost that would otherwise be wasted between wide rows.

Another reason he can plant closely is that the grass strips "ventilate" the garden—let more sun and air through to its plants. So fungus diseases don't bother him. At the same time, those grassy walks check erosion nicely. This is a garden without little brooks running through it during a heavy rain. The rain is held there.

As soon as one of the vegetable beds is harvested, the old plants are pulled up to prevent their needlessly draining soil fertility, and are turned into compost. The bed is then prepared with the rotary tiller and sown to winter rye. This provides a soil-enriching humus material when it's turned under next spring. In the meantime, while growing, it keeps the bed green and attractive.

Sometimes, he gets a double "crop" of humus this way. For example, rye sown after peas, around August first, would grow too high and be a nuisance to turn under. It's turned under before it's past a foot high. It starts rotting. Meanwhile, enough of its roots sprout again to provide a winter cover crop which is turned under next spring.

Space between vegetable rows varies according to the plant. For example, members of the cabbage family—cauliflower, broccoli, etc.—are staggered, with plants 18 inches apart in two rows. The same 54-inch-wide strip holds 3 rows of sweet corn. The corn is planted successively, as are other crops, to give successive ripening. These different-age plantings of corn are in different beds, so as to disperse their shading of other vegetables. Along the same idea of giving plants maximum sunlight, the strips were laid out with a compass to run exactly north and south.

Stratton files a tidy planting chart away each year, so there is no lengthy session with seed catalogs. He knows what varieties he has used, which he likes, which were planted where—so that he can rotate vegetables through the different beds.

Here's a gardener who has a place for everything, everything in its place, from the sun dial at the front to compost heaps in the rear. Vines greedy for space, like cucumber and squash, are kept off at one side.

At the other side of the garden are perennials—one strip is occupied by two varieties of strawberries, and the last strip of all is reserved for a bed of asparagus. Beyond this, out by themselves, are the young fruit trees, each properly mulched with a mound of sawdust.

In front of the garden are two attractive beds which serve as sort of an introduction, separating the main lawn from the double-purpose lawn. One bed has rhubarb. The other contains annual flowers grown for cutting.

In the bountiful garden, there is scant waste. Surplus is handled by Mrs. Srtatton in several tasteful ways. Among her "tools" are two faithful recipes one for canned vegetable soup, the other for 5-vegetable drinking juice— "rrot, parsley, tomato, onion, celery. —William Oilman

A Wonderful Way of Living

In 1949 we bought 20 acres of rolling land along a highway two miles from our town of Decatur, Indiana. The location was ideal for us as my husband, Speck, works at the General Electric plant in Decatur and our two eldest children were soon to start at the St. Joseph school there.

The first things I planted were a row of 4 apple trees, two Bartlett pears and a couple of cherry trees. We had a strip plowed up for a garden 75 by 275 feet. The rest of the farm is laid out in 5 small fields, where we rotate corn, oats and hay. This generally provides enough feed for the livestock we raise.

In my garden I grow asparagus, strawberries and rhubarb. Vegetables are sweet corn, tomatoes, green beans, lima beans, red kidney beans, peas, carrots, beets, turnips, potatoes, cabbage, peppers, celery, okra, zucchini, acorn and butternut squash, pumpkins, cucumbers, watermelons, muskmelons, lettuce, radishes and onions. This year I am adding eggplant, cauliflower and Brussels sprouts to my list as I feel that by now my soil is getting good enough to try these harder-to-grow things.

I forgot to mention popcorn. The children love to spend winter evenings eating popcorn while they watch TV. I also grow my own herbs. They are so much better than the ones you buy. I dry basil, marjoram, parsley, thyme, chives, mint and rosemary.

We have some grapevines starting to produce good crops now. I make jelly and can all the juice I can. We get a little fruit from our apple, pear and peach trees.

I've never kept exact figures on how much I spend on my garden, but here are some facts I can remember for this year. My seed orders totaled $12.50; I bought $4.50 worth of colloidal phosphate and potash, plus another $6 or $7 for straw. There won't be any money spent on expensive chemical fertilizers or sprays, you can bet.

Perhaps you are wondering if growing much of our own food saves on the grocery bill. Well, I should say it does! I allow $10 to $15 a week for groceries. In a pinch, I have spent even less. I know a few families the size of ours of moderate means who buy everything and spend at least $30 to $35 a week or food. I'm sure they don't get nearly as good food as we have.

I freeze corn, peas, strawberries, applesauce, lima beans, asparagus and rhubarb. I can green beans, kidney beans, beets, pears, peaches, tomatoes, grape juice, kraut and pickles. For as long as they will keep, we store potatoes, squash, carrots, beets, turnips, celery and cabbage in the basement.

I think this way of living is wonderful. I know we could never afford to paying for our new house with our present income if we did not save money on our food this way and if we had rnedica1 and dental bills to pay all the time. And as you can see it really is a wonderful way to raise a family. —Lois Hebble

A Few Facts About Food Costs

The following are statistics issued in a report by the Virginia Polytechnic Institute Extension Service:

1. The average urban family spends about one-fourth of their total income for food.

2. Families with less than $2,000 a year income spend one-half of it for food.

3. Even so, many people are poorly fed; they get enough food to satisfy hunger but not the right kind to meet body needs.

4. The average homemaker in the United States feeds 4 people each day.

5. In 1957, 36 million homemakers spent 37 billion dollars in food stores. That is about $21 a week or $1,021 a year (over 5 million of these are farmers, who produce some of their food).

6. The amount you should spend to get an adequate diet depends on the following:

a) The time available tor preparing meals.

b) The tastes and food habits of the family.

c) Facilities at home for preparing and storing food.

d) What food you produce at home.

7. The United States Department of Agriculture estimates of food costs for a low-cost adequate diet in December, 1954, were as follows:

a) For a family of two ................................. $13 a week

b) For a family of 4 with pre-school children ............. $18 a week

c) For a family of 4 with school children ................. $21 a week

This is the lowest amount that could be figured to get an adequate diet. For more variety, the "moderate" cost diet would cost $16, $22, and $26 for the groups above. According to VPI, a 100 by 220-foot plot of good land can produce enough vegetables for a family of 5. That's around $325 worth at the market. Figure you'll put in about 12 days of hand labor after the land's ready for planting.

The Statistical Abstract of the United States for 1959, published by the United States Department of Commerce, lists these figures (in pounds) of the per capita consumption of major food commodities:

Meats—152.0 pounds per capita

Fish (edible weight): 10.0 pounds

Poultry products: eggs (number) 348,

chicken 28.5,

turkey, 5.6

Fruits: fresh, total, 92.3,

Processed: canned fruit, 22.4 canned juices (excl. frozen), 12.1 frozen (incl. juices), 8.5

Vegetables and melons: fresh, 130.7 canned, 44.2 frozen, 7.6

To get some idea of the amount of cash income spent by the American consumer on food, look at the following statistics compiled by the editors of

Fortune magazine. These figures are in terms of 1953 dollars, with income computed after taxes:

|

Income Group |

Average Income |

1953 |

|

$0-1,000 |

$ 510 - $ 4,060.78 in 2008 Dollars |

89.9% |

|

$1,000-$2.000 |

1,520 - $12,102.71 in 2008 Dollars |

52.2 |

|

$2,000-$3,000 |

2,525 - $20,104.84 in 2008 Dollars |

33.1 |

|

$3,000-$4,000 |

3,495 - $27,828.28 in 2008 Dollars |

30.2 |

|

$4,000-$5,000 |

4,450 - $35,432.29 in 2008 Dollars |

23.7 |

|

$5,000-$7,500 |

6,125 - $48,769.16 in 2008 Dollars |

25.9 |

|

$7,500-$ 10,000 |

8,410 - $66,963.04 in 2008 Dollars |

22.9 |

|

$10,000 and over |

18,275 - $145,511.24 in 2008 Dollars |

14.7 |

![]()